Independence Within Alignment: Governance Irreversibility in European AI Policy

AI Safety, Ethics and Society (AISES) – Final Project Submission Winter 2025

[Feedback request: My goal is to establish a place in the greater AI international governance conversation. I am a former USAid diplomat and I am adjusting to the new world outside of international development by focusing on a new career within the world of International AI policy and governance outside of the USA. My dream is to contribute to the global conversation and provide a voice to remind policy makers that humans are an important resource too, and should be valued over profits. Thank you]

Abstract

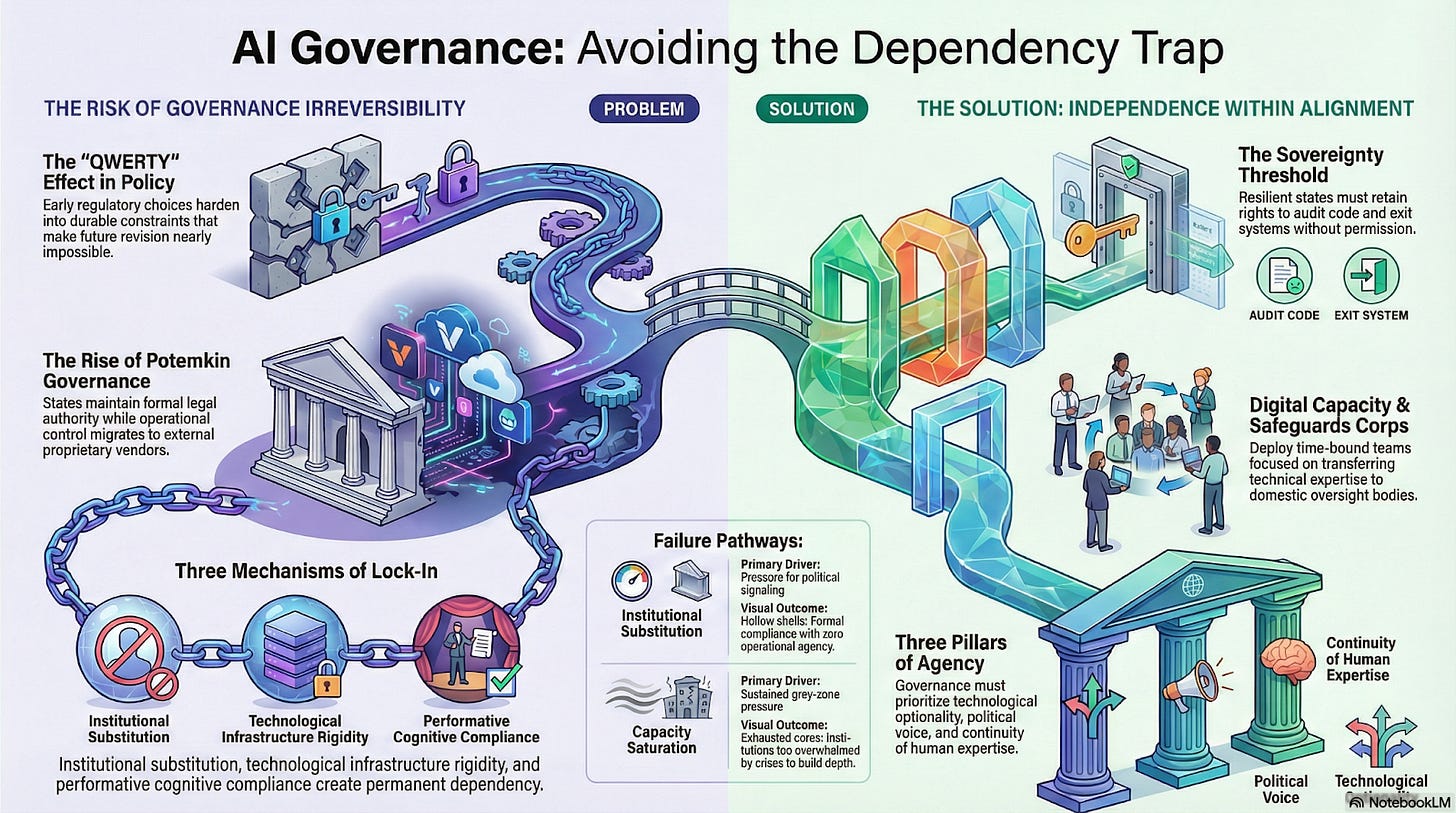

Europe’s leadership in artificial intelligence governance has been defined by ambitious regulatory action, most notably through the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (European Union 2024). While harmonization is necessary to manage systemic risk and assert democratic oversight, this paper argues that blanket implementation across uneven institutional landscapes introduces a distinct and under-examined national security risk: governance irreversibility and the rise of Potemkin governance.

Drawing on political economy, security studies, and empirical cases from Albania and Moldova, the paper shows how early AI governance decisions—often made under economic or geopolitical pressure—can harden into durable institutional, technological, and cognitive constraints (David 1985; Pierson 2000). These constraints leave states formally compliant yet substantively dependent, responsible for systems they cannot meaningfully audit, adapt, or redirect. Under gray-zone conditions, where hybrid pressure exploits delay, dependency, and infrastructural rigidity, such governance hollowing becomes a strategic vulnerability rather than a technical inconvenience (NATO 2023).

The paper advances Independence Within Alignment as a security-oriented governance principle designed for instability. It argues that resilient AI governance must preserve domestic institutional capacity, technical optionality, and political voice while participating in shared European standards (Council of Europe 2024; OECD 2019). To operationalize this approach, the paper proposes treating human governance capacity as sovereign infrastructure and establishing Digital Capacity & Safeguards Corps—time-bound, deployable teams mandated to build indigenous oversight capability with explicit exit guarantees.

The central claim is clear: global stability can no longer be assumed. AI governance systems must be designed for adaptability rather than permanence, strengthening domestic institutions instead of replacing them. Alignment grounded in agency endures; alignment without capacity hardens into dependency.

I. Governance Irreversibility as a Security Risk in European AI Policy

The QWERTY layout was designed in the nineteenth century not for speed or optimization, but to slow typists down and prevent mechanical jams. It persists not because it is superior, but because billions of people have been trained to use it and entire systems have been built around it. Switching would impose prohibitive retraining, coordination, and infrastructure costs. Society is locked in (David 1985). European AI governance now faces a structurally similar risk.

Europe’s contemporary AI governance trajectory is shaped not only by technological acceleration, but by the rapid institutionalization of the EU Artificial Intelligence Act as the continent’s primary governing framework for artificial intelligence (European Union 2024). The Act represents a necessary effort to harmonize standards, manage systemic risk, and reassert democratic oversight in a domain long dominated by private actors. Yet its blanket implementation across deeply uneven institutional landscapes introduces a distinct and under-examined national security risk: governance irreversibility and the rise of Potemkin governance.

Governance irreversibility occurs when early regulatory, institutional, or technological decisions harden into durable constraints that limit future political and security choice. In the AI context, these constraints do not arise from malicious intent or regulatory failure. They emerge from path dependence—the gradual accumulation of institutional habits, sunk costs, and technical infrastructures that make revision increasingly difficult over time (Pierson 2000). What begins as a pragmatic alignment choice can, under pressure, evolve into long-term dependency.

The risk is not the ambition of the EU AI Act itself, but the speed and uniformity of its implementation relative to domestic capacity. By prioritizing rapid harmonization and enforceable conformity, the Act establishes a common legal floor for AI governance. In states with mature regulatory institutions and deep technical expertise, this anchors meaningful oversight. In states with thinner institutional capacity or sustained external pressure, a different outcome emerges.

Potemkin governance arises when states align legal frameworks and deploy AI-enabled infrastructures while domestic oversight capacity, technical expertise, and institutional learning remain underdeveloped. Governments retain formal responsibility for outcomes, but operational control settles into proprietary systems, external compliance platforms, and inherited technical architectures. Public authorities keep the title; vendors keep the keys. Over time, responsibility concentrates at the state level while effective agency migrates outward.

Viewed through a geopolitical lens, the stakes intensify. Europe’s AI governance choices unfold amid shifting U.S. technology policy, strategic competition with China, and renewed emphasis on digital and data sovereignty. At the same time, gray-zone conditions—disinformation, cyber operations, economic coercion, and technological influence—compress decision timelines and reward solutions that appear immediate, standardized, and enforceable. Under these conditions, governance systems that privilege speed and formal alignment over institutional learning risk sacrificing long-term resilience for short-term coherence (NATO 2023).

The central challenge is therefore not regulatory ambition, but premature rigidity. When governance choices harden before domestic audit capacity, technical visibility, and exit options are established, states may find themselves aligned in form but dependent in practice—responsible for systems they cannot meaningfully interrogate, adapt, or redirect.

II. Governance Lock-In and the Mechanics of Irreversibility

Governance lock-in does not arise all at once. It develops through a sequence of rational decisions that gradually become self-reinforcing, progressively narrowing the range of future governance options. Political economy describes this process as path dependence: early choices shape what actors learn, which investments become rational, and which alternatives fade from view. Over time, deviation becomes not only expensive, but politically and administratively impractical (Arthur 1989; Pierson 2000).

The QWERTY keyboard illustrates this logic at a societal scale. A small design choice—made under specific technical constraints—triggered downstream investments in training, manufacturing, and complementary systems. Once embedded, the cost of switching exceeded the cost of inefficiency. The system endured not because it was optimal, but because it was entrenched.

Applied to national governance systems—particularly those governing healthcare, border control, defense, or public administration—this logic carries far higher stakes. When AI systems are embedded early into core state functions, lock-in reshapes sovereignty, accountability, and security. These risks are amplified by the speed of AI adoption, which far outpaces earlier general-purpose technologies.

AI governance is especially vulnerable because technical infrastructure, regulatory routines, and epistemic norms evolve together. AI tools move rapidly from experimentation to operational deployment, embedding themselves into workflows while their risk profiles remain fluid. Adoption is uneven across regions and institutions, producing asymmetries in who governs systems and who merely operates them. (Farrell and Newman 2019).

Governance irreversibility in AI emerges through three interrelated mechanisms.

Institutional lock-in arises when states lack the capacity to implement or oversee AI governance independently and therefore rely on external authorities for expertise, enforcement, or legitimacy. Under the EU AI Act, regulators are expected to audit algorithms, assess bias, and verify data governance—tasks that require sustained technical expertise many administrations do not possess. Governments respond rationally by hiring consultants, relying on centralized interpretation, or procuring turnkey systems that promise compliance. Enforcement remains formally national, but execution migrates outward. Temporary support hardens into permanent dependence. The consultants never leave. Internal expertise fails to develop. Responsibility remains; agency erodes.

Technological lock-in compounds this dynamic through infrastructure and procurement. AI governance is inseparable from physical systems: cloud platforms, compute clusters, proprietary software stacks, and global data transmission networks. These infrastructures determine what oversight is technically possible and how easily systems can be modified or replaced. Once deployed, they persist for years or decades, anchoring governance authority to specific architectures and vendors.

Cognitive or policy lock-in completes the picture. Governance frameworks adopted rapidly without sufficient administrative or epistemic capacity become performative rather than operational. Laws exist, registries are created, ethics boards are named—but oversight remains shallow. Compliance is demonstrated through documentation rather than independent interrogation.

Together, these mechanisms transform early AI governance decisions into durable constraints. What appears orderly and efficient in the short term becomes brittle under pressure. Alignment achieved without capacity does not produce resilience; it produces dependency.

III. Albania: Institutional Substitution Under Alignment Pressure

Albania illustrates how governance irreversibility can emerge through institutional substitution rather than institutional failure. As an EU candidate state, Albania operates under sustained pressure to demonstrate regulatory convergence, modernization, and anti-corruption reform (European Commission 2023). In this context, AI governance functions not only as a technical undertaking, but as a signal of political credibility. The result is not resistance to alignment, but over-performance in form.

Albania’s 2024 launch of Diella, an AI-enabled “virtual minister,” exemplifies this dynamic. Introduced as a tool to enhance transparency and reduce corruption in public administration, the initiative was framed as a governance breakthrough aligned with European digital transformation goals (Politico 2025). Its visibility and symbolism were deliberate. Yet the project revealed a deeper structural pattern: institutional substitution in place of institutional strengthening.

Rather than expanding the technical capacity of existing oversight bodies—through trained auditors, statutory authority, and internal model evaluation capability—the initiative displaced accountability upward into a symbolic AI interface. Authority appeared centralized and modernized, even as operational control remained opaque. Regulators retained formal responsibility, but lacked access to underlying models, training data, procurement logic, or system constraints. Oversight depended on compliance documentation rather than independent interrogation.

This trajectory reflects rational adaptation under asymmetric constraints and mirrors broader integrity challenges in the region (OECD 2023). Faced with limited staffing, thin technical expertise, and strong incentives to align quickly with EU expectations, outsourcing compliance and governance signaling becomes the path of least resistance. Over time, however, substitution hardens into dependency. External vendors and consultants fill governance gaps meant to be temporary. Internal expertise fails to develop. The consultants never leave.

The result is a hollow shell: institutions that retain legal authority but lack operational agency. Responsibility remains national; control migrates outward. This is Potemkin governance not as deception, but as structure—regulatory completeness in appearance, fragility in practice. Once embedded, these arrangements are difficult to unwind without significant political and financial cost. Alignment, achieved too quickly, becomes irreversible dependency.

IV. Moldova: Capacity Saturation Under Hybrid Security Pressure

Moldova presents a fundamentally different pathway to governance irreversibility—one shaped by capacity saturation under sustained hybrid pressure. Its 2024 AI and Data Governance White Paper reflects disciplined alignment with EU frameworks and explicit attention to democratic safeguards (CSoMeter 2024).

Unlike Albania, Moldova’s trajectory is characterized by genuine political will to govern. Its 2024 AI and Data Governance White Paper reflects disciplined alignment with EU frameworks, careful sequencing, and explicit attention to democratic safeguards. Rather than symbolic innovation, Moldova has pursued cautious, procedural consolidation.

Yet Moldova’s governance environment is defined by conditions Albania does not face to the same degree: persistent foreign interference, cyber operations, disinformation campaigns, and economic coercion. AI governance unfolds not in a neutral administrative space, but under what security doctrine describes as gray-zone pressure—an active campaign for the depletion of sovereignty by an adversary (NATO 2023). These dynamics have strained institutions during recent electoral cycles, a challenge documented by international democracy assessments (Freedom House 2024).

The consequence is not hollow institutions, but overloaded ones. During Moldova’s 2025 parliamentary election cycle, AI-assisted information operations, illicit financing, and cyber disruptions intersected with governance domains increasingly mediated by digital systems. The state responded by strengthening cybersecurity coordination, strategic communication, and alignment with European partners. Each response was rational. Collectively, they imposed expanding governance obligations on already constrained institutions.

Regulatory bodies faced staffing shortages, high turnover, and overlapping mandates spanning cybersecurity, electoral integrity, data protection, and emerging AI oversight. Governance remained real and sincere, but depth eroded. Capacity was consumed by crisis response rather than institutional learning. Oversight existed, but it was stretched thin across too many fronts. This is not voluntary dependency. It is forced exhaustion.

Under sustained hybrid pressure, Moldova is compelled to prioritize immediate stability over long-term capacity building. External support becomes essential, but dependence grows not because institutions are replaced, but because they are never allowed the breathing room to mature. Alignment continues, but sovereignty thins—not through symbolic excess, but through relentless strain.

The distinction matters. Albania’s risk lies in choosing speed and visibility over institutional depth. Moldova’s risk lies in being denied the time and space required for depth to form. One pathway produces hollow shells; the other produces saturated cores. Both converge on the same outcome: governance irreversibility under pressure.

True AI sovereignty therefore requires more than legal alignment. It requires a clear sovereignty threshold: ownership of training data, the right to audit code, and the authority to modify or exit systems without external permission. Independence within alignment captures this requirement. It is not resistance to European frameworks, but a demand that participation preserve agency across time.

Where political alignments shift rapidly while infrastructures persist, AI governance must sustain operational ownership, not just procedural compliance. Moldova demonstrates that even good-faith alignment, under adversarial pressure, can harden into dependency if capacity is treated as expendable rather than strategic.

V. Gray-Zone Pressure and the Physical Reality of Lock-In

In AI governance, irreversibility operates through time compression at the front end and time drag at the back end. Decisions are made quickly under political, economic, or security pressure. Their consequences unfold slowly and resist reversal. This temporal mismatch—not technical failure—defines the structural vulnerability that allows governance hollowing to take hold and persist. Gray-zone actors exploit this asymmetry by targeting critical infrastructure rather than territory (NATO 2023).

Recent European experience with strategic infrastructure makes the stakes visible. Energy policy following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine required rapid political realignment and emergency diversification away from Russian supply (European Commission 2022). Those decisions were necessary. Yet the physical infrastructures built under crisis conditions—pipelines, terminals, long-term contracts—continue to shape European energy policy years later. Political alignment shifted quickly; infrastructural reality did not.

AI procurement now functions as today’s energy pipeline. A comparable infrastructural commitment, embedding long-lived technical dependencies that constrain future choice (Farrell and Newman 2019).

Decisions made to secure compute capacity, cloud access, or regulatory compliance embed long-lived technical and contractual dependencies that constrain future political and strategic choice. Once installed, these systems persist across electoral cycles, policy reversals, and security realignments. The governance consequences are not immediate, but they are durable.

Gray-zone pressure reshapes AI governance by exploiting this asymmetry. Unlike overt conflict, gray-zone strategies operate below the threshold of war through disinformation, cyber operations, economic leverage, and technological influence. They do not seek immediate collapse. They reward gradual dependency, delayed correction, and narrowed future options.

For states navigating AI governance under such conditions, time becomes the central vulnerability. Political alignments, electoral outcomes, and security postures can shift rapidly. Technical systems—data centers, cloud contracts, compliance tooling, audit infrastructures—persist. Once physical and institutional infrastructures are deployed, they anchor governance choices long after the political context that justified them has changed.

European security assessments increasingly recognize that gray-zone operations target critical digital infrastructure and information environments, not territory. Undersea cables, cloud infrastructure, data centers, and platform ecosystems now constitute strategic terrain. The vulnerability exists before any overt action occurs. As one NATO assessment noted, the cables are already on the seabed; the exposure precedes the attack (NATO 2023).

AI governance systems embedded in public administration follow the same logic.

AI procurement is not merely a policy choice; it is an infrastructural commitment. Compute reliance, data storage, model deployment, and compliance platforms tie governance authority to specific technical architectures. These systems require long planning horizons, substantial capital investment, and stable contractual arrangements. Once installed, they determine what governments can see, audit, and change. Political leaders may revise priorities quickly; governance systems follow at a slower pace.

Gray-zone pressure accelerates this mismatch. Disinformation campaigns, election interference, and economic coercion compress decision timelines and favor solutions that appear immediate, standardized, and enforceable. Alignment with trusted partners offers reassurance. Uniform standards promise stability. Yet these same pressures discourage experimentation, delay institutional learning, and raise the political cost of revision once alignment has been publicly signaled.

AI intensifies the problem because its governance requirements evolve alongside the technology itself. Generative models, automated decision systems, and data-driven analytics embed themselves into administrative workflows while their risk profiles remain fluid. Governance structures designed around early assumptions struggle to retain visibility as systems evolve. Oversight drifts toward compliance formalities while substantive understanding lags behind operational reality.

The costs of change compound across three dimensions:

Financial: replacing data centers, renegotiating long-term cloud contracts, retraining personnel, and rebuilding oversight institutions.

Temporal: the years required to design, approve, and deploy alternative infrastructure or governance architectures.

Political: loss of credibility, disruption of international coordination, and domestic resistance to admitting dependency.

Gray-zone actors exploit this compounding effect. Influence campaigns rarely aim to control systems outright. They aim to delay correction, deepen reliance, and constrain choice. Governance systems that appear stable in the short term become brittle over time when built around infrastructures that cannot adapt at the speed of political change.

The cases of Albania and Moldova illustrate how this vulnerability manifests through different pathways. In Albania, symbolic innovation substitutes for institutional depth, accelerating adoption while limiting audit authority. In Moldova, disciplined alignment under adversarial pressure saturates institutions, expanding formal obligations while exhausting capacity. In both cases, gray-zone pressure magnifies the consequences of early governance choices by narrowing the ability to revise them later.

The result is a form of strategic exposure that accumulates quietly. Governance frameworks remain intact. Institutions continue to operate. Yet the range of viable responses shrinks as systems harden. AI governance choices made under pressure begin to function as political constraints rather than policy tools.

In an environment defined by persistent hybrid pressure, resilience depends less on perfect foresight than on preserving the capacity to adapt. Governance systems that privilege speed and uniformity over optionality risk converting short-term alignment into long-term vulnerability. The challenge for European AI governance is therefore not simply to coordinate quickly, but to do so in ways that preserve the ability to change course when conditions inevitably shift.

VI. Independence Within Alignment: Governing for Agency Under Instability

Independence within alignment describes a governance posture designed not for equilibrium, but for instability. It recognizes that coordination across Europe remains essential, while accepting that political trust, technological trajectories, and security conditions will continue to shift. Rather than treating alignment as a terminal state, this approach treats it as a living system—one that preserves national agency while participating fully in shared European standards. It aligns with emerging European and international frameworks emphasizing human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in AI governance (Council of Europe 2024; OECD 2019).

The core premise is simple: states must retain the capacity to govern what they adopt.

Alignment establishes common objectives, baseline protections, and interoperable rules. Independence ensures that implementation, oversight, revision, and exit remain anchored within domestic institutions. The combination produces resilience rather than fragmentation. Alignment without independence hardens into dependency; independence without alignment fractures collective safeguards. Governing under contemporary AI risk requires both.

This posture matters because AI governance now operates at the intersection of law, infrastructure, and security. AI systems shape administrative decision-making, information environments, and public trust. When governance authority migrates outward—through procurement structures, compliance tooling, or inherited technical architectures—states lose the ability to respond proportionately to local risk, adversarial pressure, or system failure. Independence within alignment re-centers that authority without abandoning coordination.

Practically, this governance posture rests on three mutually reinforcing conditions: optionality, voice, and continuity.

Optionality requires that governance systems preserve meaningful exit and revision pathways. AI governance frameworks must allow states to change vendors, reconfigure oversight mechanisms, and recalibrate risk classifications as systems evolve. This does not mean constant change. It means avoiding architectures—technical, legal, or contractual—that foreclose adaptation once adopted.

Voice ensures that states participate not only in rule adoption, but in rule interpretation and evolution. Alignment must include mechanisms for feedback from implementation contexts, particularly from states operating under asymmetric pressure. Without voice, harmonization becomes extraction of compliance rather than co-production of governance.

Continuity treats human governance capacity as sovereign infrastructure. Institutions must be designed to persist across electoral cycles, funding shocks, and security crises. This requires sustained investment in people: auditors, procurement specialists, technical regulators, and legal experts capable of interrogating AI systems independently. Capacity that exists only during pilot phases or donor-funded windows is not capacity—it is exposure.

These principles clarify why governance irreversibility is not merely a regulatory concern, but a security one. When states lose optionality, voice, or continuity, AI systems begin to constrain political choice rather than serve it. Alignment achieved under those conditions may be legally sound, but strategically brittle.

Operationalizing independence within alignment therefore requires institutional design, not exhortation. One concrete mechanism is the establishment of Digital Capacity & Safeguards Corps: time-bound, deployable teams mandated to build indigenous AI governance capability within national institutions, with explicit exit guarantees. Unlike permanent advisory missions or outsourced compliance structures, these corps would be structured around capacity transfer, not substitution.

Deployed at the request of states operating under alignment pressure, such teams would focus on:

training domestic auditors and regulators,

establishing internal model evaluation and procurement review capability,

embedding audit access and data governance rights into contracts,

and designing governance architectures that remain functional after external support withdraws.

Crucially, these deployments would be finite by design. Their success would be measured not by longevity, but by the ability of domestic institutions to assume full operational control. Exit is not failure; it is the objective.

Within the European context, this model complements rather than challenges existing frameworks. It strengthens the EU AI Act by ensuring that compliance is operationally meaningful, not performative. It reduces reliance on permanent external vendors and consultants. It transforms alignment from a one-time achievement into an adaptive process grounded in institutional ownership.

While such a mechanism could ultimately operate at a global level—with regional hubs supporting states across different governance environments—its immediate relevance lies within Europe’s own margins. EU applicant and neighboring states operate at the sharpest edge of AI governance risk: under-resourced, exposed to hybrid pressure, yet expected to implement some of the world’s most demanding regulatory frameworks. Treating their governance capacity as expendable weakens the entire European project.

Independence within alignment therefore reframes the purpose of harmonization. The goal is not uniformity for its own sake, but resilient diversity within a shared legal order. Systems designed for permanence in a volatile world do not endure. Systems designed for adaptation do.

In an era where global stability can no longer be assumed, AI governance must be built to bend without breaking. Alignment grounded in agency endures. Alignment without capacity hardens into dependency.

VII. Conclusion: Designing Governance for a World That Will Not Stand Still

European AI governance is entering a phase where its greatest risks no longer stem from absence of regulation, but from regulation that hardens too quickly in unstable conditions. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act establishes a critical legal floor for accountability, rights protection, and systemic risk management. Yet when implemented across uneven institutional landscapes under geopolitical pressure, harmonization alone cannot guarantee resilience. In such contexts, governance itself can become a vulnerability.

This paper has argued that governance irreversibility constitutes a national security risk. Early AI governance decisions—made under alignment pressure, crisis conditions, or capacity constraints—can harden into durable institutional, technological, and cognitive lock-ins. Once embedded, these structures constrain future political choice, limit auditability, and narrow exit options long after the circumstances that justified them have changed. What appears orderly in the short term may become brittle under pressure.

The cases of Albania and Moldova illustrate two distinct pathways to the same strategic exposure. Albania demonstrates how institutional substitution under alignment pressure can produce Potemkin governance: formal compliance paired with hollowed capacity and permanent external dependence. Moldova demonstrates how capacity saturation under sustained gray-zone pressure can exhaust even good-faith institutions, forcing reliance outward not by choice, but by necessity. One pathway is voluntary; the other is coerced. Both converge on governance systems that retain responsibility while losing agency.

Gray-zone actors exploit precisely this convergence. They do not need to capture institutions or sabotage systems outright. They exploit the temporal mismatch between fast political decision-making and slow infrastructural change. AI governance systems, once embedded into public administration through procurement, cloud reliance, and compliance tooling, function as long-lived commitments. They shape what states can see, audit, and change—often long after political alignments shift. Dependency accumulates quietly. Correction becomes costly. Optionality erodes.

The central lesson is not that alignment is misguided, but that alignment without capacity is unstable. Governance frameworks designed for permanence in a volatile world do not endure. They harden. They fracture under pressure. They convert short-term coordination into long-term vulnerability.

Independence within alignment offers a security-oriented alternative. It reframes harmonization as a living system rather than a terminal state. It insists that states retain operational ownership of the systems they adopt: the capacity to audit, adapt, and exit. It treats human governance capacity as sovereign infrastructure rather than a transitional expense. Treating human governance capacity as sovereign infrastructure echoes development and governance research emphasizing institutional durability as a prerequisite for resilience (UNDP 2023). Oversight failures linked to insufficient capacity have been repeatedly identified in EU governance audits (European Court of Auditors 2023). Operational mechanisms such as time-bound Digital Capacity & Safeguards Corps translate this posture into practice, ensuring that alignment builds institutions rather than substitutes for them.

The implications extend beyond EU applicant states. Europe’s margins are not peripheral to AI governance; they are its stress tests. They reveal what happens when ambitious regulatory frameworks meet institutional asymmetry, hybrid pressure, and compressed timelines. Designing governance that holds at the margins is not an act of concession—it is a condition for durability at the core.

Global stability can no longer be assumed. Political alignments will continue to shift. Technological systems will continue to persist. In this environment, AI governance must be designed not for static compliance, but for adaptation under pressure. Alignment grounded in agency endures. Alignment without capacity hardens into dependency.

The choice before European AI governance is therefore not between ambition and restraint, but between rigidity and resilience. The future will belong not to systems that appear strongest at the moment of adoption, but to those that retain the ability to change course when the world inevitably does.

References

Arthur, W. Brian. 1989. “Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events.” Economic Journal 99 (394): 116–131.

Council of Europe. 2024. Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence, Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law. Strasbourg.

CSoMeter. 2024. Moldova: AI and Data Governance White Paper. Chișinău.

David, Paul A. 1985. “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY.” American Economic Review 75 (2): 332–337.

European Commission. 2022. Strategic Dependencies and Capacities. Brussels.

European Commission. 2023. Albania 2023 Report. Brussels.

European Court of Auditors. 2023. Digital Capacity and EU Governance Risks. Luxembourg.

European Union. 2024. Regulation (EU) 2024/… Artificial Intelligence Act. Official Journal of the European Union.

Farrell, Henry, and Abraham Newman. 2019. “Weaponized Interdependence.” International Security 44 (1): 42–79.

Freedom House. 2024. Freedom in the World: Moldova. Washington, DC.

Mazzucato, Mariana. 2018. The Value of Everything. London: Penguin.

NATO. 2023. NATO Strategic Concept and Hybrid Threat Assessment. Brussels.

OECD. 2019. OECD Principles on Artificial Intelligence. Paris.

OECD. 2023. Integrity and Anti-Corruption in Eastern Europe. Paris.

Pierson, Paul. 2000. “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics.” American Political Science Review 94 (2): 251–267.

Politico. 2025. “Albania Appoints the World’s First Virtual AI Minister.” Brussels.

UNDP. 2023. Digital Governance and State Capacity. New York.

United Nations General Assembly. 2024. Global Digital Compact. New York.